Reports and Working Papers

Publications from CGWR Faculty

Worker Voice: What it is, what it is not, and why it matters: Summary Report

The term “worker voice” has been used by practitioners, policymakers, and scholars to cover a broad range of institutions and mechanisms, from suggestion boxes and corporate social responsibility programs to trade unions and enforceable brand agreements.

To analyze worker voice institutions and mechanisms, the report establishes a three-step process. The first step involves analyzing the context, including the regulatory regime, patterns of worker rights violations, union dynamics, and structures of exclusion in society. The second step entails analyzing the mechanisms or organizational structures, forms of participation and governance, and remedy mechanisms. The third step is to study outcomes for workers and society as a result of these mechanisms.

Using the six-component framework and the three-step analytical process, the report finds that democratic trade unions and collective bargaining are the most effective mechanism for supporting worker voice.

Worker Voice: What it is, what it is not, and why it matters

Worker voice entails the capacity of workers to speak up, articulate, and manifest collective agency to improve the terms and conditions of work and livelihoods and contribute to more equitable and democratic societies. Trade unions and collective bargaining most clearly fit this definition of voice. The question this report seeks to answer is: What are the most effective forms and mechanisms of worker voice in today’s global economy and growing non-standard and precarious work? Common jobs today include work in outsourced segments of global supply chains, the informal economy, authoritarian regimes, and sectors often not covered by labor laws, such as agriculture and domestic work. How might undocumented migrant workers—who live and work under the constant fear of deportation—organize and exercise voice? And how are effective worker voice and respect for rights to freedom of association related to efforts to reduce child labor? The report finds that mechanisms that enhance the ability of workers to elect, represent, protect, include, enable, and empower their members and their organizations are the most effective forms of voice. It explores this argument via seven case studies covering multiple economic sectors in diverse geographic areas. The report concludes by providing key considerations for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers. It also identifies research gaps, emphasizing that future research on worker voice is needed in under-studied regions of Africa, and Central and South America.

Worker voice is a topic on which scholars and practitioners have written for well over a century, and the interest in the topic has only grown over time, particularly since the 1980s. Yet, what exactly is meant by ‘worker voice’? And when and why is it effective, and when is it not? This literature review seeks to provide answers to these questions. It does so through an exploration of scholarship from diverse fields, including sociology, economics, political science, history, industrial relations, labor studies, and business management. It provides a systematic overview of the topics discussed under the concept of “worker voice.” Cutting across our approach to the literature is an attempt not only to define worker voice and its components and explore its numerous manifestations, but also to understand outcomes. When do worker voice mechanisms result in concrete and significant changes in terms and conditions of employment?

The outbreak of COVID-19 has rapidly increased the precariousness of gig workers around the world, especially that of food and grocery delivery workers. At the same time, these workers have become more visible, recognized, and even applauded for their key role during the pandemic, being classified as “essential workers.” While much of the world population spent numerous months in lockdown, food delivery workers continue to provide crucial services to communities through their delivery of food, medicine, and other important supplies all the while exposing themselves to a severe, life-threatening, and highly contagious virus. While the worldwide development of several vaccines seeks to curb the impact of the coronavirus in important ways, vaccine rollout has been unsystematic and slow, leaving many food delivery workers without protection. Drawing on thirty-nine semi-structured interviews and five months of participant observation, this report explores the experience of food delivery workers in Mexico, their response to COVID-19, and their broader transnational organizing efforts.

This report examines the importance of collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) for addressing poor working conditions in global supply chains. The report is organized into two parts. Part I explores the context in which the manufacturing export sector in Honduras (primarily garments) developed. This is based on an analysis of trade and financial data and an exploration of secondary sources. It examines the growth of the apparel sector, the status of labor law and workers’ rights, the structure of global supply chains, and the evolution of bargaining in the sector. Part I concludes by analyzing the path-breaking agreement between Honduran unionists and the multinational corporation Fruit of the Loom, known by the parties as the ‘Washington Agreement.’ Part II examines the twelve years of collective bargaining that followed the signing of the Washington Agreement. It does so through field research and an original survey of 387 workers in Honduras, which was done through a model of ‘worker-driven’ research. Part II documents the positive impact of CBAs on wages, benefits, the reduction of gender-based violence and harassment in the world of work, pandemic relief, and a range of other benefits for workers. It is one of first extensive and systematic examinations of collective bargaining agreements in Honduras since the 2009 signing of the Washington Agreement.

This report maps the strawberry sector from the position of field workers in Mexico’s berry sector. Their labor generates profit for their employers and, along with labor throughout the chain, the companies at other stages of the strawberry commodity chain. The report begins with mapping the global strawberry sector, then focuses analysis at the national and local levels. The employment relations section highlights labor laws governing the sector, with a focus on recent domestic and regional legal reforms. The next section maps out unionization in the sector. The two subsequent sections detail distribution of value across the sector and private certifications used in it. A concluding section summarizes implications and outlines recommendations. The appendix provides additional data presentations, and the annex details main companies in the sector.

Every day all across the globe, hundreds of millions of workers leave their homes—or in some cases, stay in their homes—to toil in informal jobs. Informal jobs span dozens of industries and contexts and are increasingly common in many national economies around the world. Definitions of informal employment vary: the broad category includes employees of informal firms as well as informally employed workers in formal firms, some self-employed individuals, and people who work for households who do not necessarily consider themselves employers. Informal workers are thus in a difficult situation when it comes to enforcing their rights, as these rights may not be guaranteed, even in principle, by law. Despite a lack of state recognition or protection, informal workers across the world are organizing in vibrant and powerful movements to create better working conditions. This report is the result of an unprecedented six-nation study of informal workers and their struggles for change. Researchers in China, India, Mexico, South Africa, South Korea, and the United States engaged in countless hours of interviews, examination of government data, field observations, and other forms of original research to better understand the global but diffuse informal worker movement.

Every day all across the globe, hundreds of millions of workers leave their homes—or in some cases, stay in their homes—to toil in informal jobs. Informal jobs span dozens of industries and contexts and are increasingly common in many national economies around the world. Definitions of informal employment vary: the broad category includes employees of informal firms as well as informally employed workers in formal firms, some self-employed individuals, and people who work for households who do not necessarily consider themselves employers. Informal workers are thus in a difficult situation when it comes to enforcing their rights, as these rights may not be guaranteed, even in principle, by law. Despite a lack of state recognition or protection, informal workers across the world are organizing in vibrant and powerful movements to create better working conditions. This report is the result of an unprecedented six-nation study of informal workers and their struggles for change. Researchers in China, India, Mexico, South Africa, South Korea, and the United States engaged in countless hours of interviews, examination of government data, field observations, and other forms of original research to better understand the global but diffuse informal worker movement.

This research report is the latest in a series of reports by the Center on retailer and brand purchasing practices during the COVID-19 pandemic, and their impacts on workers and supplier factories. In this report, Center Director, Mark Anner, finds a large majority of suppliers surveyed reported that brands have demanded price dis- counts substantially larger than the year-over-year reductions they typically seek. As a result, over half reported that they are being forced to accept prices for orders that are below the cost of production. Suppliers also reported that many customers have imposed payment schedules that will require suppliers to wait additional weeks or months to be paid for their work, in an industry where payment terms are already severely skewed in favor of buyers. In sum, the survey results indicated that many brands and retailers are treating their suppliers’ increasing desperation as a source of bargaining leverage. The survey also showed that these financial pressures threaten the viability of many apparel suppliers and are likely to cause, or have already caused, large-scale dismissals of workers.

Center and WRC published a research brief documenting $16.2 billion in cancelled orders and retro-active price reductions by garment brands and retailers. See research brief. The result has been a dramatic loss of income and jobs for millions of garment workers. The report was covered by The Guardian. See Guardian article.

The global COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on global garment supply chains, and the situation will get far worse before it gets better. As clothing outlets have been shut by lockdowns in developed market economies, sinking demand for apparel, brands and retailers have moved quickly to cancel or postpone production orders – refusing, in many cases, to pay for clothing their supplier factories have already produced. The result has been the partial or complete shutdown of thousands of factories in producing countries. As a result, millions of factory workers have been sent home, often without legally-mandated pay or severance.

Despite more than two decades of private voluntary approaches to address workers’ rights abuses in apparel supply chains, workers in the lower production tiers continue to face poor working conditions and chronic violations of their rights. Bangladesh has been emblematic of low wages and poor working conditions, culminating in the collapse of Rana Plaza in 2013. With the five-year anniversary of the catastrophe approaching, the question arises as to whether the intervening years have seen meaningful gains for workers. This report finds that gains have been severely limited in regard to wages, overtime hours, and work intensity in part due to the sourcing practices of the brands and retailers that sit at the top of global supply chains. A partial exception is in the area of associational rights, where, in the aftermath of Rana Plaza, pressure resulted in minor pro-union labor reforms. This report finds one area where gains for workers have been dramatic: building safety. This is largely the result of an unprecedented binding agreement, the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. The Accord, which imposes constraints and obligations on global firms that are absent from traditional voluntary CSR schemes, has overseen a massive program of safety renovations and upgrades.

The Stern Center for Business and Human Rights at New York University released a report in December 2015, “Beyond the Tip of the Iceberg: Bangladesh’s Forgo en Apparel Workers.” It argues that the factory inspection programs developed after the Rana Plaza disaster to address worker safety in Bangladesh exclude the majority of workers and are therefore reaching only the “tip of the iceberg.” We have carefully reviewed the Stern researchers’ methodology and data, and come to the opposite conclusion. Contrary to Stern’s assertions, more than 70 percent of garment workers in Bangladesh are covered by the Accord and the Alliance, and if we include workers employed in factories inspected by the ILO-advised National Initiative, the percentage of covered workers reaches 89 percent. We also find that Stern, due to a series of errors in data collection and analysis, greatly overestimated the number of formal factories and the size of the workforce.

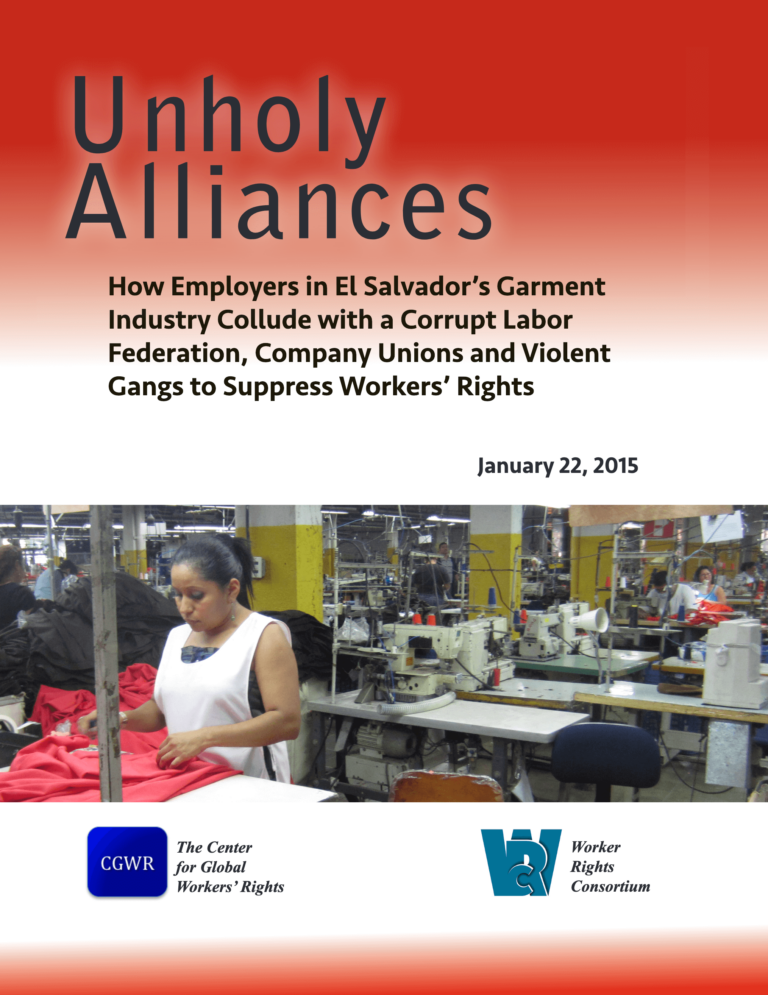

The Center for Global Workers’ Rights together with the Worker Rights Consortium announce the publication of their report, “Unholy Alliances: How Employers in El Salvador’s Garment Industry Collude with a Corrupt Labor Federation, Company Unions and Violent Gangs to Suppress Workers’ Rights.”

The privatization of Colombia’s port sector in 1993 inaugurated a process of pervasive employment flexibilization. The thousands of port workers, previously unionized on a mass scale and protected by collective bargaining agreements and indefinite employment contracts, witnessed a rapid transformation in their working conditions, highlighted by the explosion of non-standard work contracts, informal hiring and firing, and the gradual asphyxiation and/or transformation of labor unions. In Buenaventura, home to the country’s busiest seaport terminal, the flexibilization of labor relations took on a decidedly robust form.

Insertion into the global economy through global garment supply chains is often cited as a necessary step on the path toward economic development and worker well-being. Yet, in recent decades, this path has often proven elusive for developing countries. Many apparel exporting countries have remained in low value-added, low-wage, and low-development tracks despite growth in garment exports. In India, the value of apparel exports increased by 480 percent between 1992 and 2016, from USD 3.1 billion to USD 18 billion. At the same time, and, by one estimate, wages in the Indian apparel export sector only covered 23 percent of workers’ living expenses (WRC 2013: 108). And patterns of forced overtime, work intensity, and various forms of precarious work all appear to be rising.